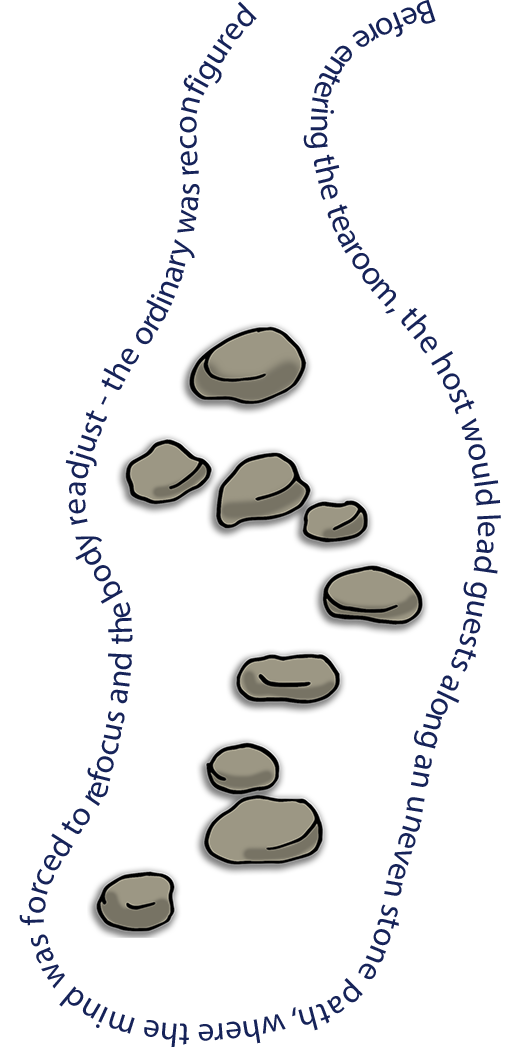

Rikyu’s new way of tea diverged from the visuals preferred by Nobunaga and Hideyoshi yet elaborated on its elitist intention. Instead of the expertly crafted smooth surfaces, the overarching aesthetics of Rikyu’s interpretation of wabi-sabi aligned more with fabricated poverty, in that it saw beauty in absence, roughness, and the everyday (8). This new chanoyu - derived from Zen Buddhist practices – went to great efforts to exude the appearance of minimal effort, but in truth, the space and ceremony were crafted by a set of highly intentional and stylised processes which dictated the look and feel of the actions and objects (9). How the tea master went about structuring his space was determined by a lengthy series of detailed yet open-ended guidelines (10). What one can ascertain from this is that the definition of wabi could not be expressed verbally, but rather it was a kind of feeling or spirit embodied by the practitioner, the space, and the objects, and only understood by a select few. In other words, wabi could be described as a fetish (11). The fetishisation of chanoyu was brought about by Rikyu through a rethinking of sensation. He went about this by reconfiguring the space where comfort and utility took a back seat to form – Taian tea house exemplifies his new attitude. Called ‘grass hut’ tea, this particular kind of wabi methodology was to imitate the removal and seclusion from ordinary life - like a hermit in his mountain hut (12).  |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

To enter the hut, the party crawled through a square hole called a nijiriguchi. This too was a play on optics, like Hideyoshi's Golden Tea Room, yet the effect was reversed, in that you made your way from light to dark. By contorting the body through a small threshold, the room would appear to be larger, and the bodies equalised as hierarchical arrangements were reduced (13).

| |

|

|