|

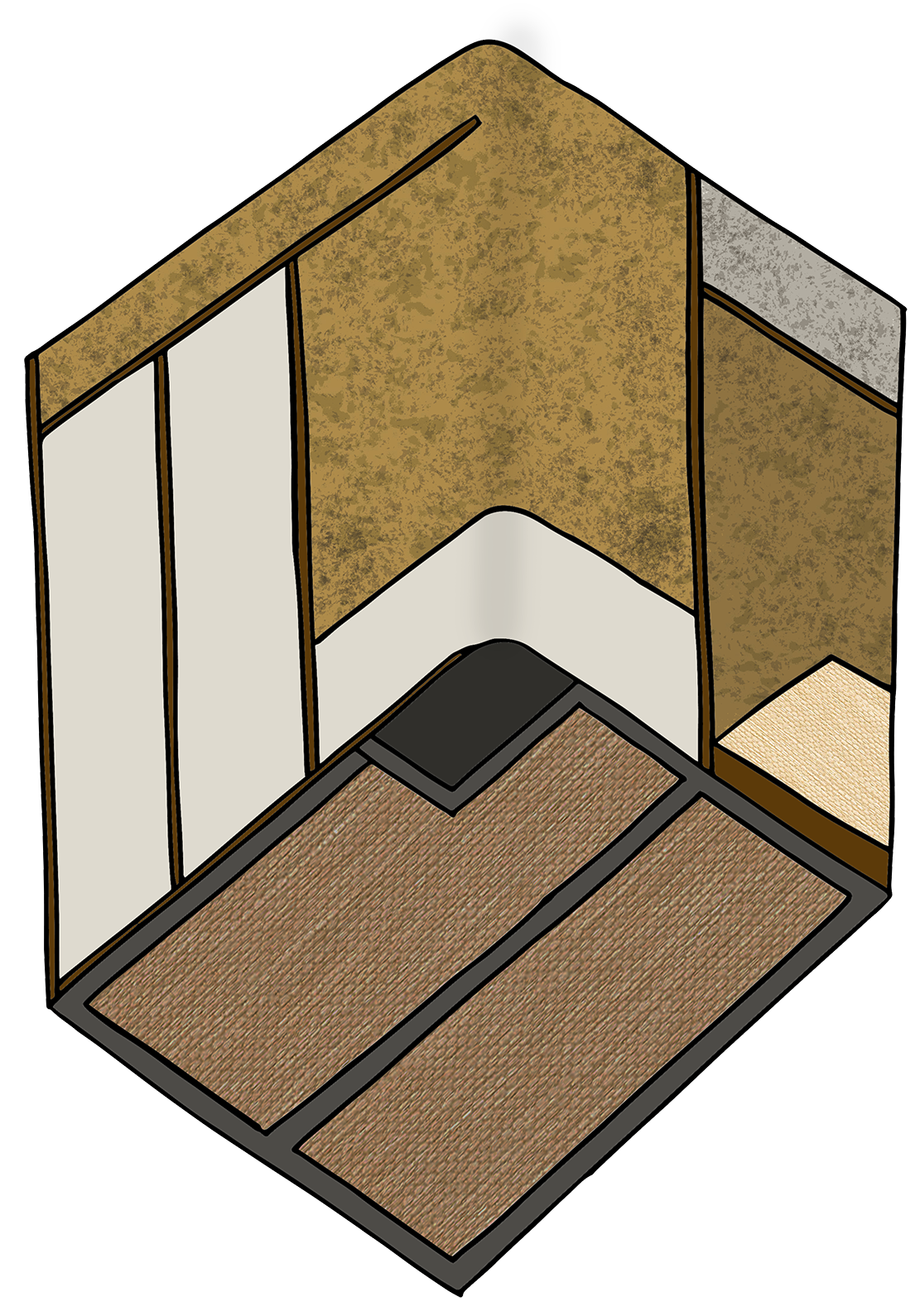

Any superfluous matter was excluded from the room to remove distraction: the seating happened across two tatami (instead of the old four-and-a-half), the utensils lay on the floor (instead of being placed on stands), and the surfaces were exposed for their true formal qualities (rather than being polished or painted over) (14). The beams and walls were left to their most basic surfaces and evidence of their making was not hidden (15).

The space was small, but Rikyu did not intend it to be uncomfortable; he didn’t want to encourage you to stay, as it was not for leisure, but rather a space for work in a non-laborious way. The close quarters further forced the body to focus on itself and the objects that surround it (16). The learned tea master curated his chanoyu to shape a mood that was fashioned by multiple considerations, for example, the persons who were attending or the time of year. The variety of utensils was an important part of his decision making; even though chanoyu went to great lengths to appear unremarkable, like the Golden Tea Room, the novelty factor was pertinent to the success of the ceremony (18). Valuable foreign wares sat alongside local, and otherwise worthless, objects, which served as a reference point which the goods as a whole and the ceremony were valued against and given new wabi meaning (19). |

| ||

|

|

|||

Like the teahouse itself, the top priority of raku wares was not to aid in comfortable use (20). These two bowls, Muichimotsu (red) and Oguro (black), were purpose built tea bowls that lacked any elements not inherent to their form. This was exceptionally radical for the time (21). These bowls were hand-built as opposed to wheel-thrown, were put through a single, low temperature firing in a small residential kiln, and were not underglazed (22). This made them wobbly, porous, and lacking in decoration, and overall, largely ineffective for prolonged and everyday use, therefore encouraging the tea drinker to meditate on the bowl’s process and act without mentally departing their environment (23). Furthermore, whoever made the bowls left their surfaces rough and pockmarked, which, under normal aesthetic standards would have been considered major surface defects and would have thus been discarded (24).

|

||||

|

These bowls were stripped back to their minimum function, but it was no means accidental. This clog-shape mino bowl has taken this distortion to another level and looks as if it had been dropped at some point while the clay was still malleable, but, in actuality, it has been misshaped with a paddle (25). Mino was known to be experimental, and in doing so it played on what was fashionable and what appealed to the consumer market – as seen in the decorative black patterns and wheel thrown form (i.e., mass production) (26).

|

|||

Before mino came seto. This small tea caddy and bowl would have been offered as affordable alternatives to imported Chinese wares. Haptically bubbly and simple in shape, the bowl offered something new for the user to experience. The tea caddy, too, diverged from the traditional as its slightly distorted with the method visible in its uneven and sludging glaze. These textures and forms meant the holder could trace the (forced) history of the object and feel connected to its making, rather than spend time speculating on its financial value (27).  |

|

|||

Shigaraki and Bizen were the first local wares acquired for chanoyu, although, in this instance the Shigaraki container here associated with Rikyu (right) was made especially for the ceremony (28). These containers assist in the forced eclecticism of wabi as their original purpose did not function as a cultural object in that it was entirely utilitarian (top). Each is incredibly tactile in that pieces of earth still protrude through the gritty clay body, and the final effects fully embrace the process as where the clay cracked, ash fell, and flames lapped against the walls during firing leaving a mottled surface effect. The Rikyu container also comes with a black lacquer lid which offers variation in texture and colour against the coarse body, nicely appropriate for a wabi ceremony.

|

|

|||

|

All other wares that were collected and stylised were based on the control object - the Chinese origin vessel (29). It was this point of contrast that laid the foundations for which the wabi aesthetic was developed against. This tenmoku bowl of the Song Dynasty would have been admired for its symmetry and demonstration of control; the glaze is aware of the form it's attached to in that it ends just before the foot ring, and has avoided gathering around the rim to ensure comfortable drinking. Once revered for technological perfection and its embodied wordliness, this tenmoku tea bowl was given new meaning within the aesthetically irregular Japanese chanoyu. |

|||

|

|

|||

Bamboo whisks and ladles mimic the exposed pillars in the tearoom. The plant’s surface has been neatly cut away, exposing the grain as well as the flexibility of the material (30).

|

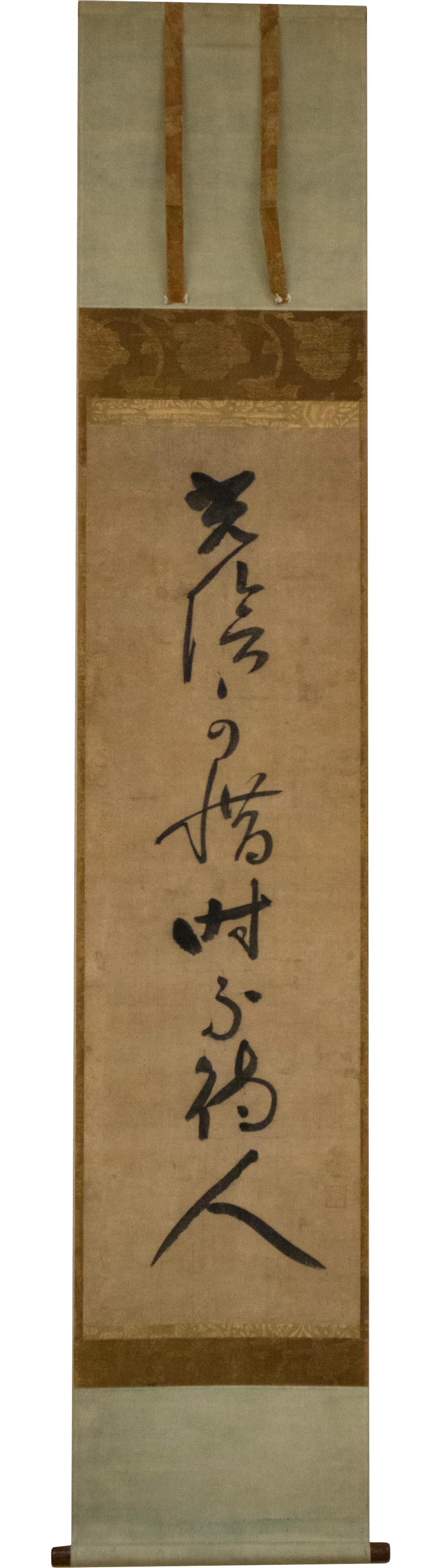

A monochrome ink painting in the tearoom’s alcove was the most important non-functional utensil in chanoyu. These works support the wabi theories present in the ceramic objects as they too gave only what is necessary whilst using the elements to find its form – in this case water, instead of earth and fire. Furthermore, its maker practiced restraint in that it avoids excesses like colour and shading. And, like the ceramics, it is aware of itself in its materiality – it was created in a brief moment where the medium was pliable to the human hand and suspended at a precipice between success and failure. All the while it poses a further point for consideration: ‘time must be cherished, it waits for no one’ (31).

|

|||

How these works were selected and arranged was determined by how an individual host best chose to execute wabi. This kind of speculative fetishisation became a staple of Japanese culture (32). next. |

||||

'

'